How to Play Guitar by Ear

While noodling around on guitar as the year wraps up, I thought of the song Auld Lang Syne and—to my pleasant surprise—banged out a fully formed fingerstyle arrangement in one go.

It wasn’t always so simple! I’ve never been interested in music theory for its own sake, I’m far from naturally gifted, and I completely relied on sheet music for many years… until eventually I got tired of hunting down and memorizing the tabs for every single song I wanted to play.

This post outlines some basic tips and tricks for producing attractive (if not exactly virtuosic) song arrangements by ear, as demonstrated in my tab of Journey’s Don’t Stop Believin’ and my cover of Final Fantasy X’s main theme:

Here we’ll apply these methods to a familiar pop tune, Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. No prior music theory knowledge required!

1. Assume C major

In piano terms, this essentially means ignoring the black keys, which typically correspond to sharps (♯) and flats (♭).

Most melodies can be played recognizably using only the white keys. This set of notes is also known as C major because a melody that uses only these notes will sound fully resolved to listeners if its final note is a C note1. Jingle Bells, Happy Birthday, Ode to Joy, you name it—all of these melodies end on C when pecked out on a piano’s white keys.

This means that we can set a song in C major by choosing C as its final note. Why does that matter? It’s less obvious than on piano, but C major is also arguably the most straightforward scale to play on guitar. The first three frets contain all the notes of C major and its commonly associated chords, minimizing hand movement.

Contrast this with the B major scale, which uses all of the piano’s black keys and four of the guitar’s frets.

Now that we know that C should be our song arrangement’s last note, how do we go about determining the rest of them?

2. Anchor the melody on C

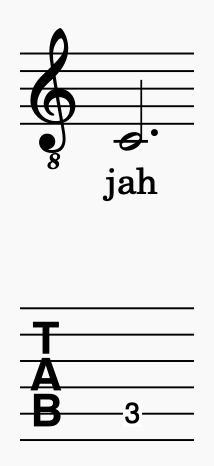

Most songs alternate between a verse melody and a chorus melody before ultimately ending with an instance of the chorus. Hallelujah’s chorus (and the song itself) ends on the last syllable of the word “hallelujah” repeated four times. If we want this last “-jah” note to be a C, we have two comfortably reachable choices within the guitar’s first three frets: the A string’s third fret and the B string’s first fret2. We’ll choose the former (lower) option since Cohen sings the final “-jah” in a relatively low register, and we want to leave room for the rest of the song’s melody to go above it.

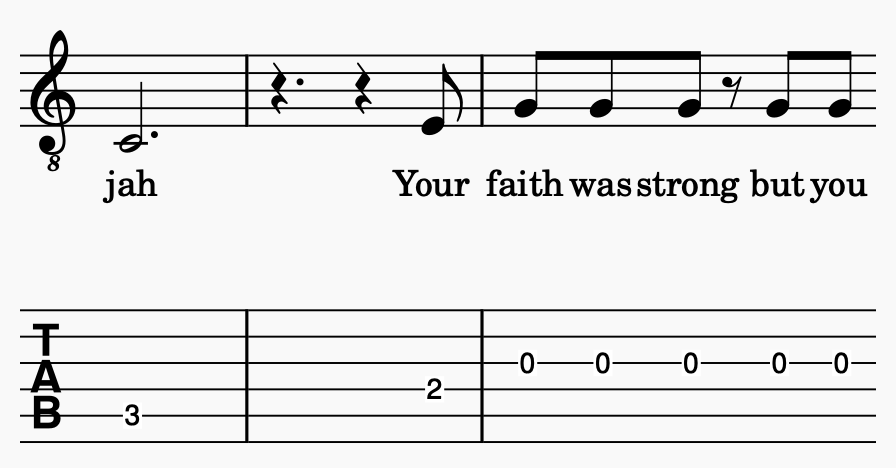

Play this low C a few times and listen to it carefully. Sing “-jah” at that pitch. Then continue singing straight into the song’s second verse, “Your faith was strong, but you needed proof”. Now we can hear how those notes should sound too, but where do we find them on the guitar?

3. Estimate interval sizes and directions

Since we’ve set our arrangement in C major, a scale that we know to be playable within the guitar’s first three frets, it’s not too hard to find that lyric’s notes through trial and error with careful listening. If we play the A string’s third fret as “-jah”, then “Your” is at the D string’s second fret, “faith” is on the open G string, and so on.

We can arrive there by guessing randomly, but that’s hardly efficient. The process becomes much faster if we hear that both “Your” and “faith” constitute small upward jumps in pitch from the preceding note. Hearing the direction and (roughly) the magnitude of such pitch changes is more important than identifying those interval sizes precisely. For example, The Killers’ Mr. Brightside repeats the same note over and over throughout its entire verse, while the climactic “or twoooooo” lyric in a-ha’s Take on Me makes a huge upward jump.

Notice that songs tend to change lyrics across verses while keeping the verses’ notes mostly the same. The opening notes of Hallelujah’s second verse are the same as those of its first verse, “I heard there was a secret chord”. Now that we’ve got the notes down for “I heard”, we can continue using each note to figure out the next one until we finally reach the song’s final “-jah”, the low C that we chose as our arrangement’s tonal center.

We’ve got a full melody line at this point, and if we were flatpicking on lead guitar then we might even call the job finished. But that’s boring—we also want to fill out our sound with chords and percussion!

4. Know the four chords

A chord is a set of notes that sound good when played simultaneously. We can’t just pluck two guitar strings at random frets and expect a decent result. Both notes should be part of the same chord.

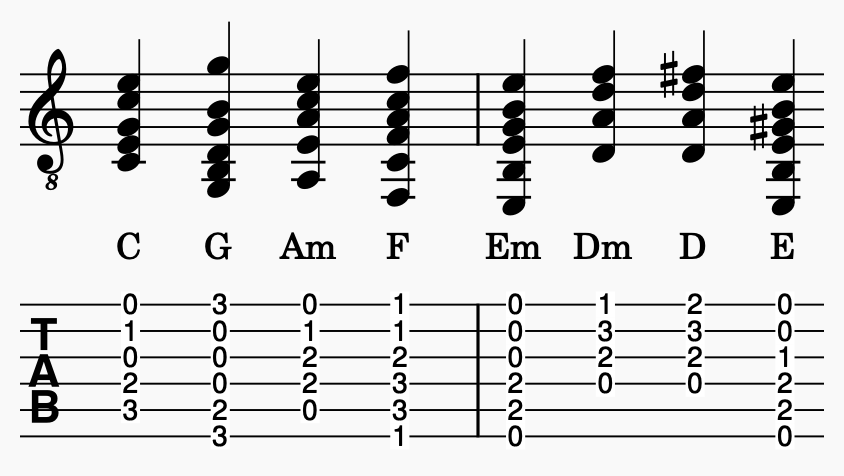

The most commonly used chords in the C major scale are C major (yes, it’s named the same thing), G major, A minor, and F major3. Very unscientifically, we can play 80% of pop songs using only these four chords, and learning a few more (Em, Dm, D, E) will get us to 95%4.

So what do we do with these chords? When do we play them, and how do we know which one to use?

5. Keep the melody on top

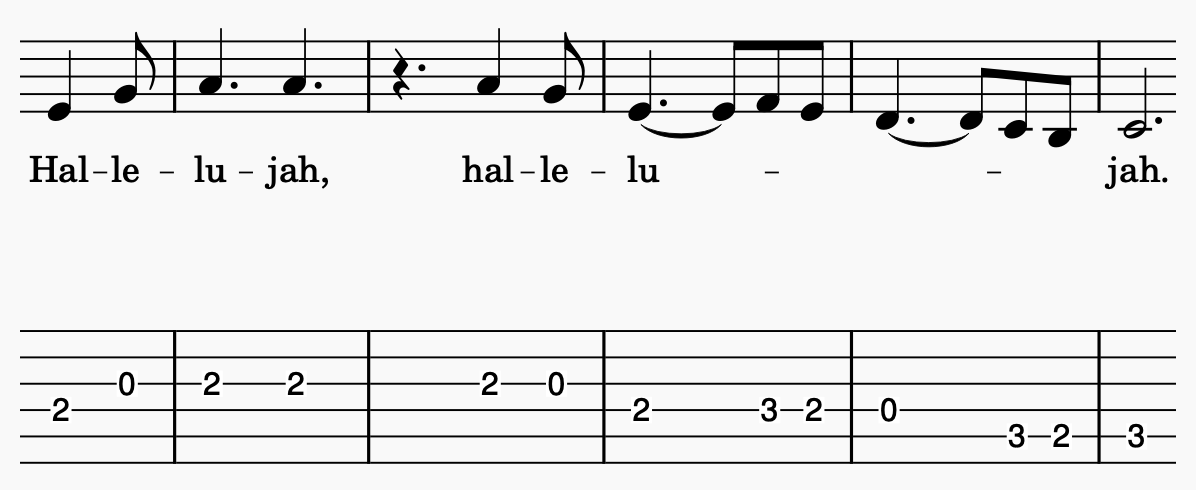

Chord changes tend to happen on downbeats, evenly spaced points in time that usually coincide with emphasized syllables. Try singing Hallelujah’s first verse:

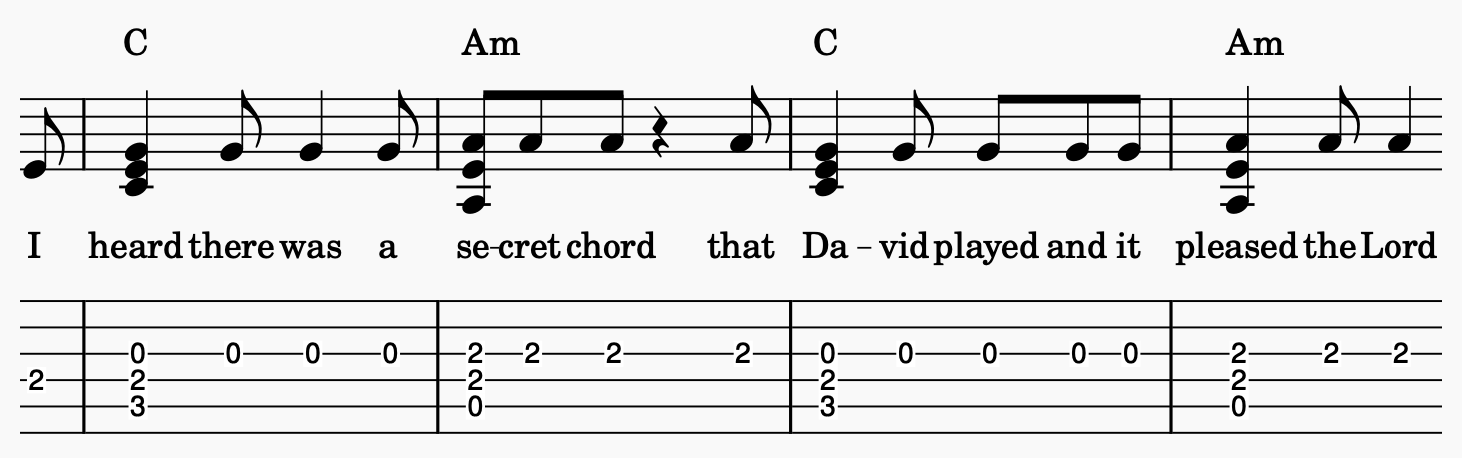

“I heard there was a secret chord that David played, and it pleased the Lord…”

The loudest syllables are “heard”, “se-“, “Da-“, and “pleased”. These points in time represent possible candidates for chord changes.

Once we have an idea of where a chord change might be happening, we can simply guess a chord to play along with the melody and see whether it sounds right! Since humans perceive high notes more strongly than low notes and we need to keep the melody audible, we should pluck only the strings of each chord that lie below the melody note’s string5.

How could we guess that Cohen chose C-Am-C-Am as the chord progression here? Trial and error works fine, but some rules of thumb may also help…

6. Understand each chord’s personality

Each of the four most common chords plays its own role in the song’s story:

Songs in C major typically end on a C chord, similar to how the melody typically ends on a C note. If you let a C chord ring out, expect the applause to begin.

The A minor chord does heavy lifting as the only sad-sounding chord of the four. Songs in C major rarely end on Am6. Songwriters often use Am in verse and prechorus sections to build tension that then gets released in the chorus.

G and F serve similar roles as happy-sounding chords that provide some flavor on the song’s way home to C. The G major chord sounds calm and expectant to me, often preceding a dramatic climax (“the baffled king com-POS-ing Hallelujah”) or the song’s final C chord (“Halle-luuuuuuuu-jah”). F sounds more casual and transient than G, as if it’s less worried about making it to C7.

Once you develop a feel for these chords’ moods, you’ll start noticing them everywhere. Hallelujah offers us a shortcut: its lyrics name the song’s own chords!

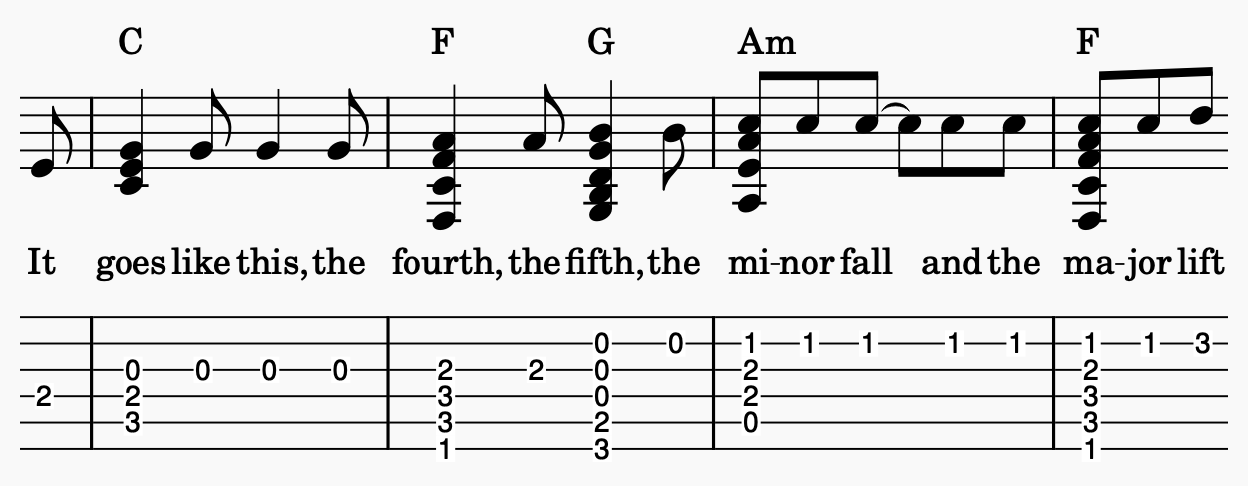

The C major scale’s fourth note counting from C is F, so “the fourth” refers to F major. Similarly, “the fifth” is G major. The “minor fall” and the “major lift” are Am and F again. (“Fall” and “lift” aren’t technical terms; they just evoke the sad and happy natures of minor and major chords.)8

7. Mix it up

Even after we put melody and chords together, our arrangement still sounds hollow. Strumming the new chord once at every chord change moves the song forward in a rather unsophisticated manner.

We can make our arrangement more interesting by arpeggiating the chords (playing their constituent notes one at a time), omitting some chords’ notes, or repeating those notes at different rhythms. We can improvise these right hand decisions on the fly instead of committing them to memory. As long as the left hand holds down the correct chord shape, anything the right hand does will sound fine.

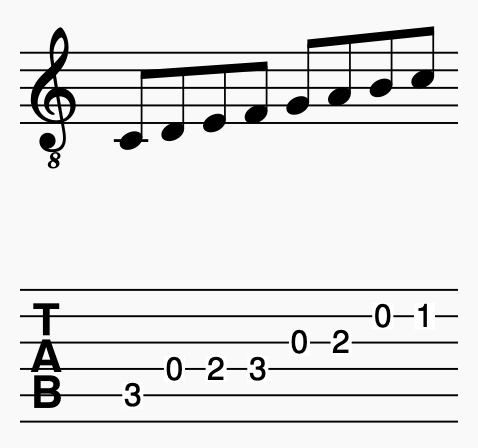

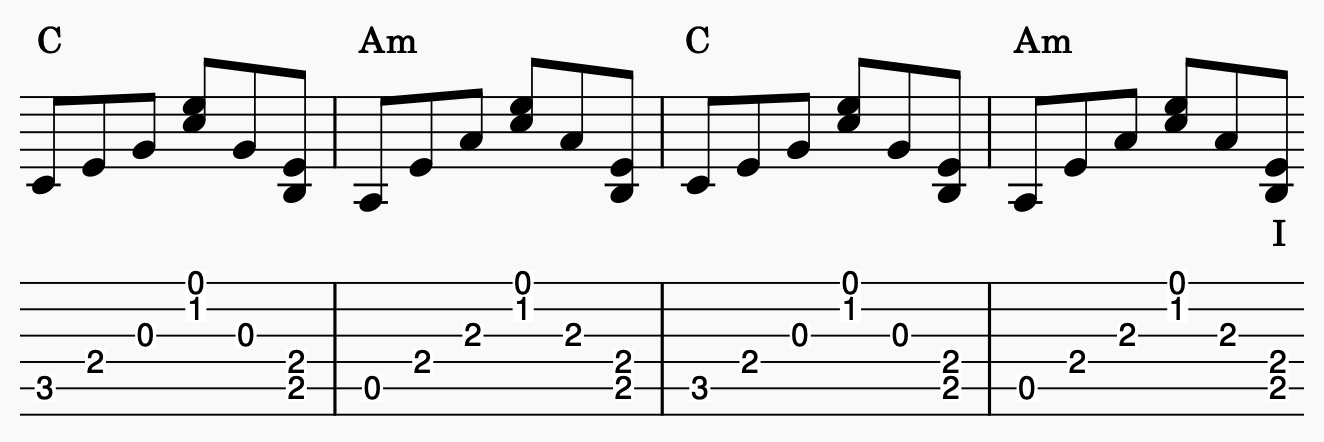

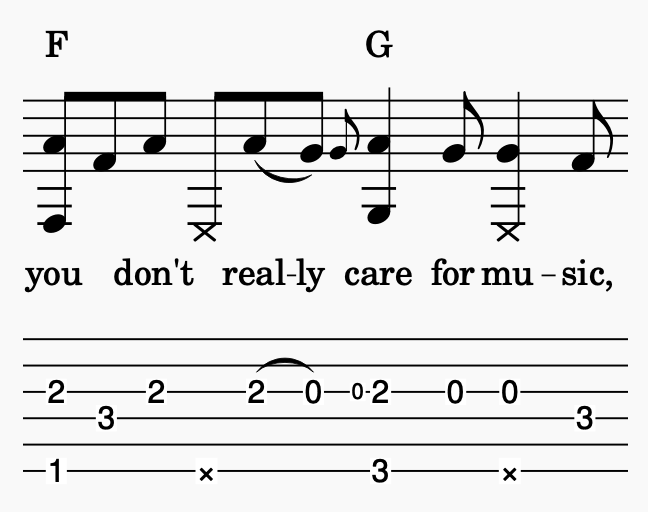

Simply arpeggiate the C-Am chord progression in a certain way and you get Hallelujah’s distinctive intro:

8. Get slapping

Slapping on guitar is like cooking with MSG. It’s like white balancing your photos. It’s a hack that instantly improves most things.

The guitar’s most basic percussive technique is to slap the lowest string or two with the left side of your right thumb, usually notated as “X” in tabs. Doing this while simultaneously plucking a note takes some practice. Other possible percussive techniques include tapping the guitar’s body with your thumb, bumping it with your wrist, drumming it with your fingers, or even scratching it with your nails, but the humble string slap alone will carry you pretty far.

When to slap? Offbeats, the evenly spaced points at which people normally clap when clapping along to a song, are a good start. We could slap throughout the entire song, but for greater variety and dramatic effect, it’s often better to wait until either the first chorus or the second verse. Many songs have a quieter, more intimate bridge section that behooves us to take a break from all the slapping. As with our chord playing, slapping is improvisable and largely up to personal taste.

9. Throw in some ornamentation

As a final touch, we can sprinkle in some small flourishes such as grace notes, slides, and harmonics. Take care not to overuse these, and again feel free to improvise rather than memorize.

Why this approach?

I used to think that playing by ear meant pulling up a song on Spotify and reproducing it note for note. That might help train your ear, but otherwise it’s a waste of time. Next week when your adoring fans ask you to play Hallelujah, will you really remember all 1000+ notes of that Spotify recording? Even if you nail every single note, will your audience notice or care? Faithfulness clearly doesn’t count for everything, given that Jeff Buckley’s version of Hallelujah is at least as popular as Cohen’s original!

This post’s methods optimize for memory efficiency, not fidelity. In computing terms, it’s lossy compression: JPEG vs RAW, MP3 vs WAV. Instead of memorizing unimportant details like the order in which the original recording arpeggiates a particular chord’s notes, we can improvise them at performance time. Sticking to the C major scale and reducing every song to its melody and chord progression lets us fit dozens—or even hundreds—of songs into our brain!

On piano, a C note is any key immediately to the left of a cluster of two black keys. There are eight of them. On guitar, C notes are located at the third fret of the A string and at the first fret of the B string, among other places. ↩

These two options’ placement on the fretboard is another reason why I prefer to set songs in C major rather than G major, the guitar’s other most common scale. The G major scale does avoid the awkwardness of barring an F major chord, and it does provide three options (on the G string and both E strings) for the song’s final note rather than two, but it also awkwardly crams two full octaves into the first three frets. Most melodies focus on a single octave, so I find it convenient that the C major scale provides a single choice of octave with ample breathing room above and below. In contrast, both of the G major scale’s two octaves are physically off-center on the fretboard. ↩

Major chords like G major may be abbreviated as Gmaj or simply G, while minor chords like A minor are conventionally abbreviated as Amin or Am. Somewhat confusingly, the letter “G” without any further context may refer to the G note, the G major scale, the G major chord, or even the G string. ↩

Taylor Swift is especially fond of and successful with the C-G-Am-F formula. She’s easily the biggest bang for your buck when playing songs by ear. ↩

Keeping the melody note on top isn’t strictly necessary, especially when the melody is at a low enough point that barely any chord notes would fit underneath. Just make sure to always play the melody note the loudest so that listeners can identify it readily. ↩

If you’re arranging a song that’s meant to sound sad the whole time, ignore everything I’m saying about C as the song’s final note and chord. The song might actually be using a sad minor scale (as opposed to a happy major scale), in which case we should aim to reach A as the final note and Am as the final chord. All other tips here remain mostly the same since the A minor scale happens to contain exactly the same notes as the C major scale. Examples of songs written in a minor scale include Linkin Park’s Numb, Simon and Garfunkel’s The Sound of Silence, Bill Withers’s Ain’t No Sunshine, and To Zanarkand as performed by myself at the top of this post. ↩

I’m generally not synesthetic, but I do mentally associate these chords with certain colors: C is white, G is yellow, Am is red, and F is blue. G is an old man, F is a young woman. Go figure. ↩

Hallelujah’s lyrics mention one more chord: the “secret chord” stated in the first verse. Can you guess what it is? It’s not actually F-G-Am-F, which is a progression of multiple chords. The secret chord is Gsus, of course :) More seriously, my money is on E7, the chord that dramatically accompanies the phrase “composing Hallelujah”. E7 marks the very first occurrence in the song’s lyrics of its namesake word “hallelujah”, it appears nowhere else in the song’s structure, it’s the song’s only chord other than the four most common ones, and it’s not named in the “it goes like this” lyrics—it’s literally a secret. ↩